The dark side of animation

Representations of the church, state and economy in popular cartoons

While we all know that animated features and shorts target younger audiences, they may have a few socio-political references disguised in their narrative. In fact, there are many religious, authoritarian, and economic implications coded in some popular animated flicks. Upon closer examination, these implications shed a darker light on the animated film; yet, this makes them more thrilling and spectacular to watch.

Disney introduced a musically fascinating and absolutely terrifying short Night on a Bald Mountain as part of the 1941 Fantasia series. In this picture, the audience witnesses a satanic uprising as numerous skeleton ghosts and demonic figures gather around a burning mountain to worship the devil. The musical score by the same name composed by Modest Mussorgsky personifies the blazing fire that rhythmically convulses across the dark mountain. While the setting is mostly black and dark blue, the fire illuminates the picture, creating a collision of neon green, red, and orange colors. This effectively creates a terrifying mood that is culminated by a projection of a huge gargoyle-like demonic figure: Satan himself. This short is quite powerful, and it warns its young audience about the dangers of submitting to unholy practices.

The fire imagery, closely linked with religion, becomes quite prominent in another Disney feature, the 1996 The Hunchback of Notre-Dame. In this film, the antagonist, Judge Frollo (ironically a clergymen in Medieval France) vocalizes his fear of being possessed by the devil in a powerful song titled Hellfire. To Frollo, the devil is a young gypsy named Esmeralda with whom the judge is infatuated. His symbolization of fire as a demonic force is quite conventional, as evident in the previous example from Fantasia, yet his persona and oppressive role in the Church appear to be one of Disney’s most controversial representations. Indeed, in the film, the church building functions both as a sanctuary and a prison for the main characters- Esmeralda and Quasimodo- with Frollo as a clear oppressor. While Frollo constantly influences the work of religious and military apparatuses in order to purge the gypsy population of Paris, his influence is limited over the church of Notre-Dame. The cathedral is represented as a relatively safe environment where the citizens can pray for a better life, as demonstrated through Esmeralda’s song God Help the Outcasts.

The representation of the church as a peaceful and safe environment is also demonstrated in a 1975 Japanese animated TV film The Dog of Flanders where the orphaned boy Nello, burdened by poverty and social prejudices, finds an escape in his art and his friendship with Aloise. Nello’s marginalized economic position sets obstacles for his friendship with Aloise since her father dislikes Nello for being poor. It also prevents Nello from buying a pricey ticket to see a beautiful Rubens painting displayed at his church. The boy’s wish is eventually granted when he walks into the cathedral at night, homeless and hungry, and looks at the displayed paintings before falling into eternal slumber with his beloved pet dog by his side.

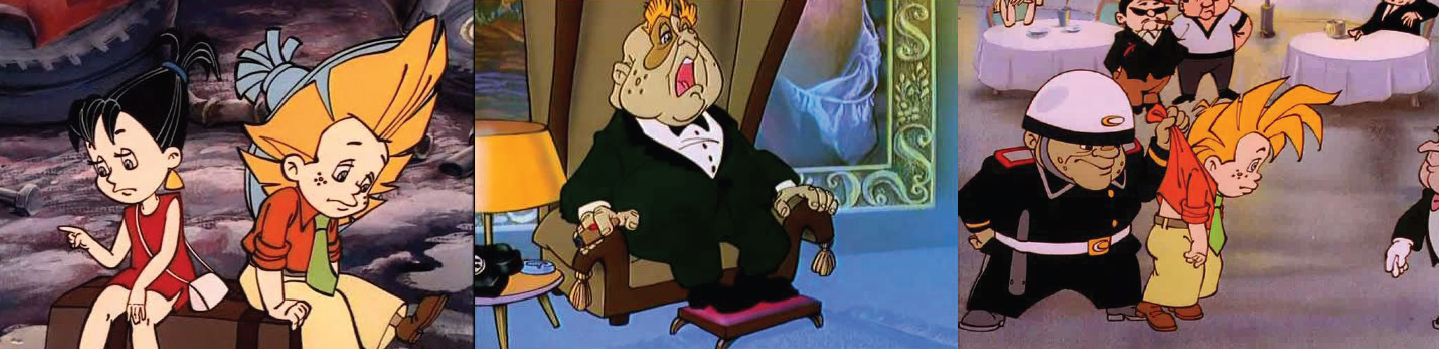

Although this Japanese film gave a general representation of poverty, the 1997 Russian cartoon Neznaika on the Moon exemplifies a satire of the capitalist system presented through a fictional society on the moon. In this feature, a silly boy named Neznaika (literally translated as ‘Notknower’ or ‘Dunno’) is raised in a society on Earth where both food and housing is communal. He later travels to the moon where he is confronted with a brutal group of grim looking businessmen who produce artificial fruit through the abuse of civilian labor. The cartoon is accompanied by charismatic characters and cheerful tunes. It ends with the ultimate defeat of the capitalists, satisfying both young and mature audiences.

The antagonistic economic system in the Russian cartoon brings us back to Disney, where the producers utilize forms of military rather than financial oppression in a few films. Since the release of an eight minute 1943 short Der Fuehrer’s Face, where proud American Donald Duck has a nightmare about becoming a Nazi soldier, Disney has evolved in its allusion to history’s most destructive regime. Indeed, the 1994 beloved picture Lion King features a compelling reference to the Nazi regime where Scar takes the place of a dictator. He stands on a rock-pedestal while announcing to the rhythmically marching hyenas to “be prepared,” just like Hitler announced his Lebensraum ambitions in the mid-1930s. Such references add another layer to animated features, turning them into captivating attractions for the young and the old.

Featured image courtesy of Neznaika na Lune, 1997