Review: One of the classics – Elena Ferrante

If you are as much of a bookworm as I am, I congratulate you, as it feels as though there are not many of us left. For a while, I thought my love and passion for literature was fleeting with the increasing popularity of digital media, even though I am studying literature. This worry was quickly cured when I discovered Elena Ferrante and her powerful story, her powerful words.

I have never thought of myself as a lover of stories, but rather a lover of words. Elena Ferrante convinced me that story is not dead, that beautiful prose that does not lull you to sleep still exists. Her words were originally written in Italian but feel like the furthest thing from a translation. They are generous, they fill the soul with an incredible amount of emotion, of nostalgia, romance, heartbreak. Her words and story break your skin in the best way; they make you think and reflect on your life, your history.

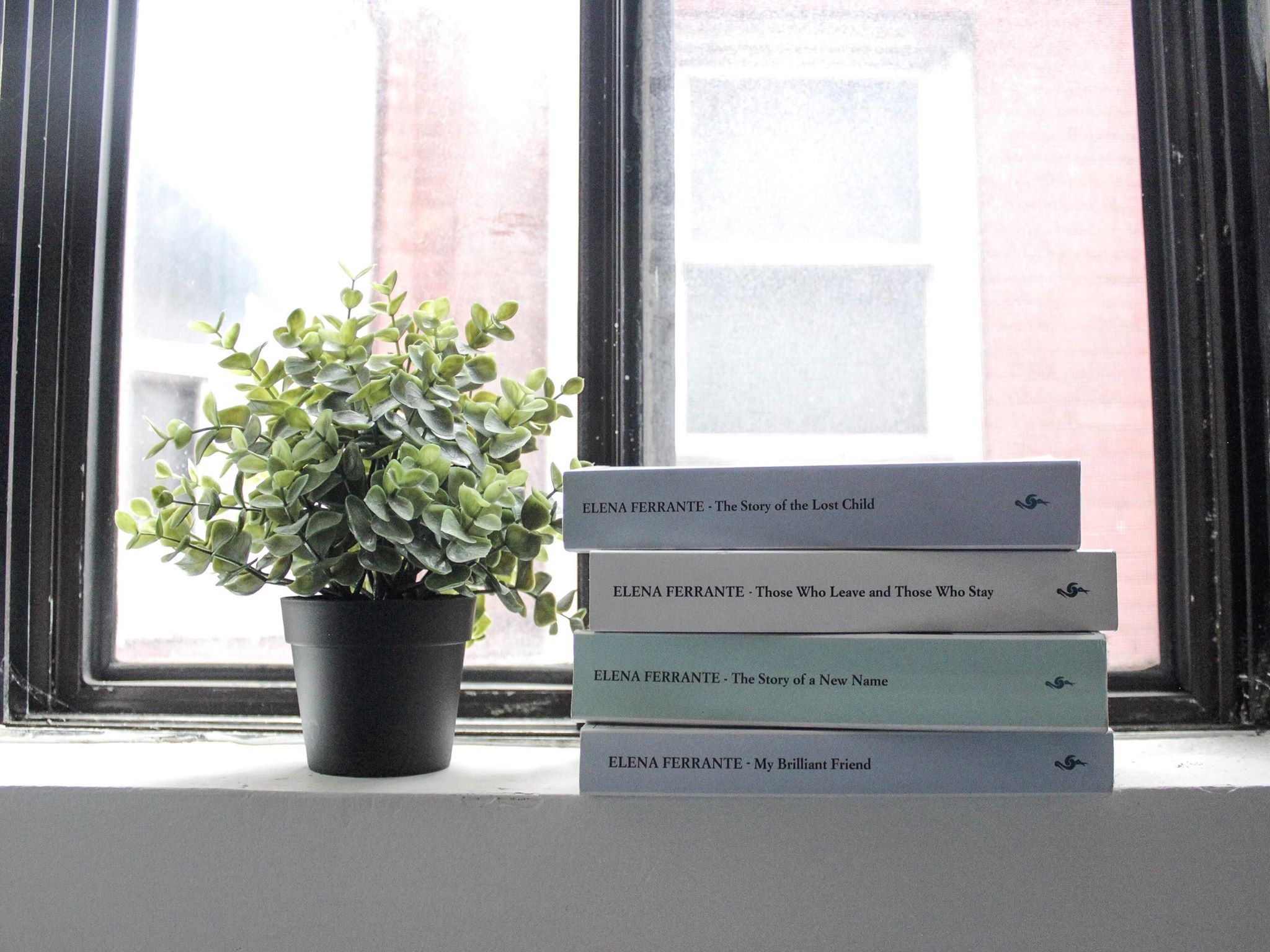

Ferrante’s Neapolitan Series consists of four books: My Brilliant Friend, Those Who Leave and Those Who Stay, The Story of a New Name, and The Story of the Lost Child. But trust me when I say this, they feel like one; the series flows like film. Each book pours flawlessly from one to another. Her description is plenty yet crisp and not overwhelming. Ferrante has a way of expressing her thoughts in such a realistic manner that they start to feel like your own. She gifts the reader her eyes.

The four parts of the series construct a beautiful narrative of two girls: Elena Greco and Lila Cerullo. The two contrasting characters, both in personality and appearance, are close friends from the very beginning of their school days. They compete for grades, study together, urge each other to do better, to go further. As they age, their lives split into two different worlds, yet they are never truly separated.

What I love about this series is the way Ferrante narrates her life events. We are given an extensive view of her thoughts, so obviously you would assume it is all about her. In most ways, it is strongly focused on Elena herself, but the real focus is on Lila. Lila is described as being a prodigy; she always studied outside of the school’s curriculum, constantly advanced her knowledge, and silently strived for more. Despite this, she chose not to continue with her schooling. She did not move out of their dingy neighbourhood in Naples and instead decided to marry and have children at a young age, sacrificing her prodigiousness for a significant portion of her life. Elena took the alternate route, a route that included advanced schooling, moving away from Naples, marrying later in life, becoming an appreciated author. Yet despite her many successes, Elena always looked at her life in comparison to Lila’s; she never felt as smart or capable as Lila. Ferrante’s stream of consciousness guides the narrative (in a less confusing way than Virginia Woolf’s) with thoughts that are catered towards questions like: what would Lila do? What would Lila think? What is Lila doing?

Ferrante adds a new layer to the realism genre. Her words portray life from friendship to firsts, and they invite you to relate to her friendships and her firsts. Ferrante does not give you a choice; her childhood recollection pricks the feelings and memories of childhood that still exist in the bottom of your belly. She portrays her emotion with such vividness that suddenly her anger is your anger, her passion is your passion, and her trauma is your trauma; your heart breaks alongside hers.

The only warning that I offer if you do decide to read her, is that her words will make you want to travel both physically and emotionally. They will invite you to break out of habit, to leave a state of being that you are not satisfied with, but, most of all, they will invite and beg and plead for you to go to Italy (at least that is what they did for me). I have never been to Europe, but Ferrante’s writing painted me a catered picture of Italy that is even more romanticized than it already is. As my eyes explored her syntax, my mind explored the streets of Naples, of Milan, of Ischia; my feet would eagerly squirm.

So, friends, do not give up on literature yet. If there is any doubt stored in your heart about the power that words and stories can hold, do not go read Homer or Virgil, for the greatest literature is one that strikes a relatability. Ferrante’s words invoke a sense of friendship, of living, of renewal. Her books are about her, but mostly, they are about you.