Review of The Tale of the Princess Kaguya (2013)

I saw a lot of great films for the first time this year. I tend to play it safe—seeking out films and directors that critics generally like—and I enjoy the vast majority of them. Now and then, I encounter a film that impacts me in a very visceral way. These films do not have a common theme or genre, and I often cannot pinpoint precisely what is so special about them. This winter break, I watched, for the first time, one of those films… Isao Takahata’s The Tale of the Princess Kaguya (2013).

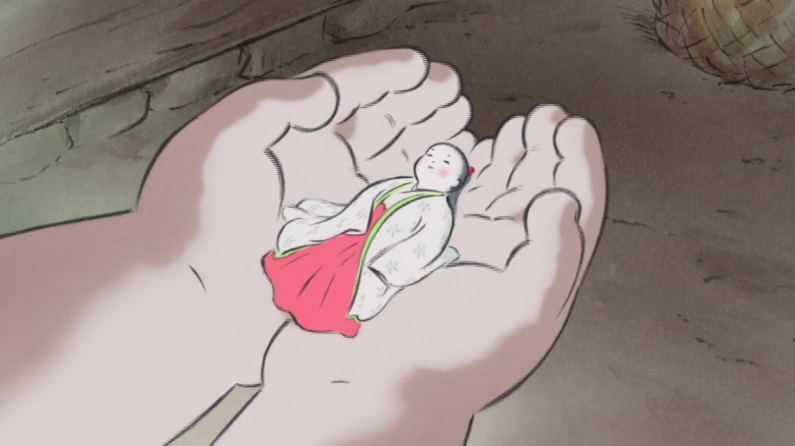

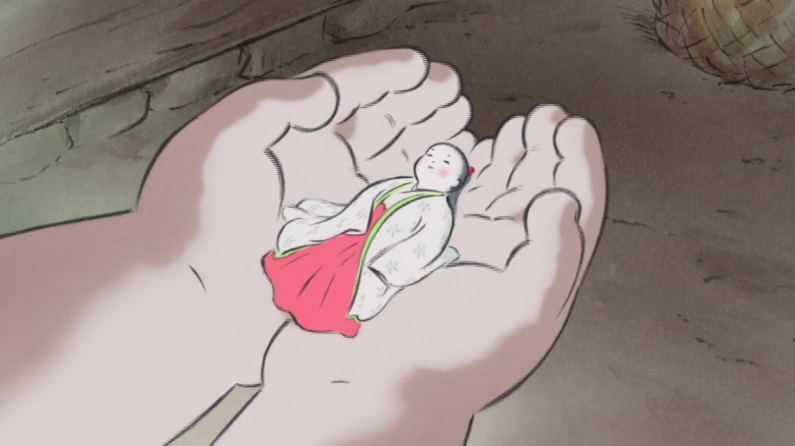

Takahata adapts the Japanese monogatari, The Tale of the Bamboo Cutter. Kaguya shares most of its major plot with its source material. A bamboo cutter living in the Japanese countryside discovers a baby in a bamboo shoot sent by a deity. Interestingly, Takahata first depicts Kaguya as a fairy-like royal princess before she becomes a baby, already destined for royalty. As the child grows, the bamboo cutter brings her to the city to develop into a royal princess. The girl is given the name “Princess Kaguya.” Suitors line up for Kaguya, and she demands that they complete impossible tasks to earn her hand in marriage.

Kaguya’s early runtime really felt like I was watching a master at work, not just because of the beautiful (and amazingly original) visuals. I cannot stress how important this relatively plotless period was for the core characters in this film. Takahata explores Kaguya’s rapid childhood, where she connects with the natural world as well as the rugged group of village boys. She especially connects with Sutemaru, who acts as a sort of guardian against the dangers of people and the natural world.

The bamboo cutter, who later becomes a frustrating actor in the narrative, shares a moment with “little bamboo” (Kaguya’s childhood nickname) that had me in tears. I know that most Ghibli viewers prefer to watch the original Japanese recordings, but I need to point out James Caan’s incredible performance as the bamboo cutter. The way his voice collapses and cracks in the most vulnerable moments really enriched the emotional impact. I need to mention the bamboo cutter’s playful rift with the village boys, where they chant for her attention, “Little bamboo!” while the bamboo cutter calls back, “Princess, come here,” with Caan’s voice breaking into tears. Besides the obvious beauty of the moment, I could not help but see the inevitable conflict: the ethereal baby could either be “Little Bamboo” or “Princess Kaguya.”

The conflict is where Takahata elevates the story and aligns the visual style and the narrative with his message. At face value, it can seem that the narrative, as well as the white-background watercolor, amplifies the purity of nature, depicting the way in which humans can corrupt and push away a “pure” being like Kaguya. In the source material, the moon princess is sent to earth by Buddhist deities as a punishment. On Earth, she is meant to experience upādāna, or material attachments. I think that Takahata challenges these ideas in his interpretation. Rather than fetishizing purity, Takahata presents the negative and positive human experiences as something holy in and of itself. Takahata also humanizes nature, illuminating its capacity to hurt as well as inflict hurt.

Rather than attempt to teach an oft-repeated lesson about humanity and its impurities, Takahata transforms The Tale of the Bamboo Cutter into The Tale of the Princess Kaguya, a visually stunning and conceptually challenging epic from a true master. Please watch this film, and please look at my favorite visual below.