Harold Who?

The decline of Harold Innis’ economics

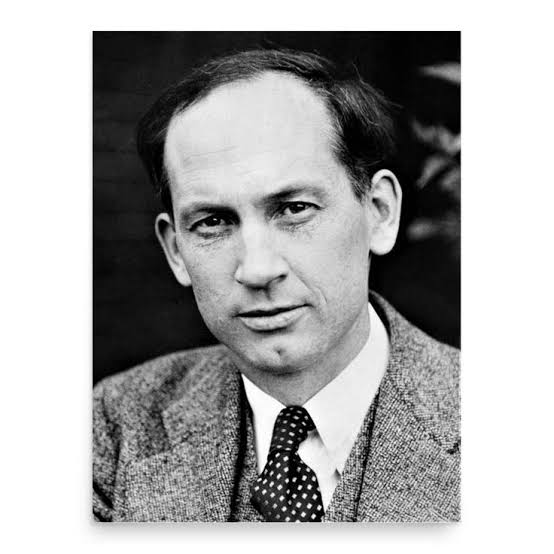

> Born near Otterville, Ontario, Innis was one of Canada’s great scholars. He joined the faculty of the University of Toronto in 1920 and became head of the Department of Political Economy in 1937. Deeply interested in the economic development of this country, he pursued his concerns through extensive field trips and research. In his published works, including The Fur Trade in Canada, The Cod Fisheries, and Empire and Communications, he left a wealth of information and theory that has significantly influenced the study of economics, history, geography, politics, and communications in Canada and beyond.

Or so reads the plaque outside of the Innis College building. But is it really true? A ctrl+F through “The Worldly Philosophers”, a book about the pre-WW2 history of economic thought, yielded no results. Neither did surveying 60 or so faculty. The only professor who filled out my form was an economist who worked on applied game theory. I also got an email response from a historian (who didn’t specialize in Canadian history).

Neither were particularly enthusiastic about him. Although the economist knew who Innis was, they did not know of Innis’ main contributions, had never cited Innis, and estimated that only around a tenth of their colleagues had heard of Innis. The historian recommended that I talk to researchers in media and cultural studies instead of modern historians, as that was where Innis was most influential except “perhaps, a small group” of historians studying Canada.

So why isn’t Innis well-known anymore? To start, most economists aren’t interested in Canada’s economic history. Two culturally similar countries, Britain and the US, have the two most important economic histories in the world. One started the industrial revolution, and the other is the world’s commercial superpower. Nearby, Latin America’s heterogeneous growth can provide arguments for almost anyone, from Marxists to anarcho-capitalists. Further away, the Asian Tigers and China attract researchers interested in development.

Innis’ narrow focus further reduced his appeal to non-Canadian scholars. A nationalist, he focused on the regional specifics of his theory instead of its international applicability, even though it preceded later and much more impactful arguments. This extended to his politics; Innis distrusted foreign solutions to Canadian problems.

His main economic contribution, the Staple Thesis, was about the interplay between imperial control, resources, society, and economic development in Canada. Canadian Encyclopedia writes, “[t]he [Staple] thesis may be the most important single contribution to scholarship by Canadian social scientists and historians.” That relationship holds back many developing countries, as many of the most resource-rich countries have terrible development paths that condemn much of their populations to poverty. However, mentions of Innis and his Staple Thesis are absent from the Wikipedia article on the Resource Curse. A 2003 paper on the development of Dependency Theory also does not mention Innis.

Besides Innis’ narrow focus, two things are responsible for his obscurity. First, his ideas were in conflict with two trends in modern mainstream economics: an emphasis on specific hypotheses over general narratives, and the use of mathematical models and statistics to estimate effects. Second, his work wasn’t taken up by heterodox schools of thought.

Modern mainstream economics generally focuses on finding the effects of specific events and policies or predicting the behavior of economic actors, instead of analyzing broad aspects of society. Although John K. Galbraith and Milton Friedman had very different opinions on economic history (and very different political opinions), their famous books on the Great Depression espoused viewpoints tightly connected to their policy recommendations. By contrast, Innis’ view of Canadian history is often descriptivist and generally treats the past as a single history, rather than a list of separate events with different costs and benefits.

The downward trend of mainstream economics seems almost inevitable in hindsight. For better or worse, the average person does not care about the details of history or the fundamental structure of the political economy. They simply want a “good economy” with high spending power, low unemployment, and policies to deal with perceived market failures. In a profession tightly connected with policymaking from its earliest days, such preferences will seep through as they influence both the composition of economists and the demand for research.

Additionally, modern economics has become more mathematical. Many papers in the top 5 journals like the American Economic Review use math and statistics to infer the costs and benefits of policies. Others describe mathematical models of either economic actors or the economy itself. This yields an approach completely different from that of the founders of political economy. Instead of trying to develop theories of broad aspects of society, economists now statistically test narrow hypotheses around specific causes and effects. It also allows economists to do research without knowing any historical context. Once, while replying to an email about free speech, a senior professor of Economics at UCL included this: “I would be pleased to continue this discussion in person… note that I am an economist and modeller and I have no idea who J.S. Mill is.” Reflecting this change, U of T’s Department of Political Economy was split into the Department of Economics and Department of Political Science in 1982, or 45 years after Innis left.

Innis can be contrasted with David Card, who will probably be the most impactful Canadian economist to ever live. Card was a key figure in the “empirical revolution” that made economic analysis a lot more reliable than before. His analysis of mass immigration and minimum wage increases shook conventional economic wisdom (he found that neither had a short-term effect on unemployment in the two cases he studied). The techniques he used are commonly found in economics papers to this day. David Card’s style probably would have annoyed Innis, who disliked the rise of statistical economics and believed its results were ephemeral time-wise, as society would change.

Even so, some heterodox economists have different approaches to economics. Yet despite having similar ideas, Innis’ theses were not incorporated into any major heterodox schools of thought. Innis was considered to be a political conservative who was skeptical of government, while heterodox economists are often left-wing interventionists; Innis once called members of an NDP predecessor organization “hot gospellers” and attacked them in print. Innis’ dislike of Keynesian economics did earn him an invitation from the University of Chicago however. Although Innis’ ideas often proved to be significant, they didn’t spread and were often reinvented separately.

Since the times of Innis, the landscape of economic thought has changed. Innis’ studies, with a focus on local over universal ideas, descriptions of the past over causal analysis of today, and verbal over mathematical reasoning, don’t align with the priorities of mainstream economics today. Although heterodox schools of thought adopted ideas similar to the ones proposed by Innis, it was not through any direct influence. Even as the internet has made it easier than ever to read Innis’ ideas across space, demand for them seems to have permanently receded. Times have changed, and with it the tastes of the economic profession.