Remembering Innisfree

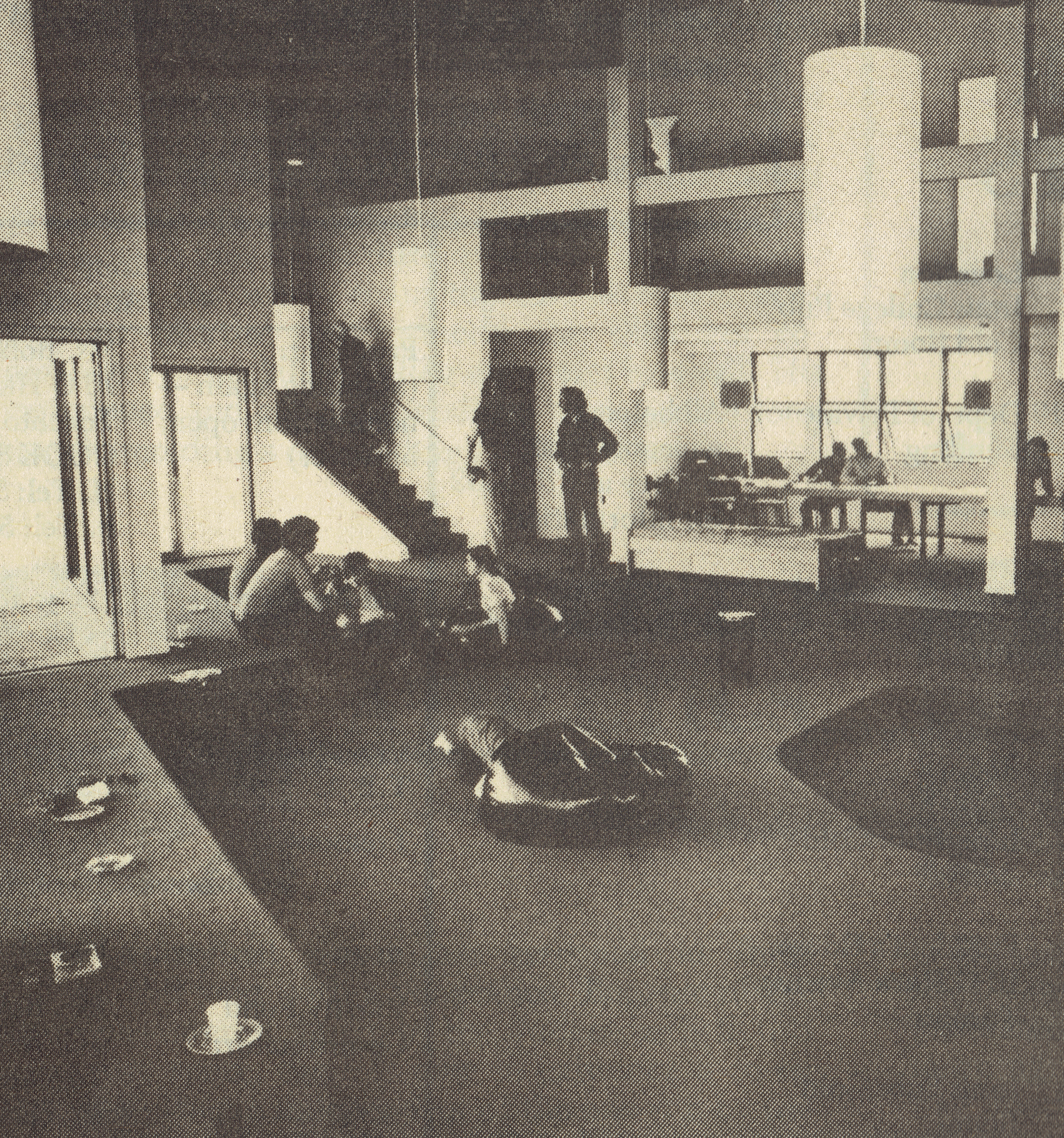

The newly constructed conference centre in the winter of 1971. COURTESY of HAROLD INNIS FOUNDATION ARCHIVES

The newly constructed conference centre in the winter of 1971. COURTESY of HAROLD INNIS FOUNDATION ARCHIVES

The year is 1971. Pierre Trudeau is the Prime Minister of Canada, gas costs 63 cents a gallon, and Innis College is the proud new owner of a 100 acre farm located in Oxford County, just west of Toronto. This is the story of Innisfree: Harold Innis’ childhood home, the site of the university’s brief experimentation with a rural conference centre, and today, the unassuming property of a family of ginseng farmers.

At the height of the 1970s, the farm was famous among Innis College students as a place to spend autumn weekends for relaxing as well as participating in a variety of activities from mellow hangouts and hikes to raving dances. Indeed, for students, weekends at the farm embodied everything the 70s featured: communal living, a laid back lifestyle, and discussions about philosophical thought.

The Story of Innisfree

Harold Innis, the Canadian academic for whom the college is named, was born on Innisfree Farm in 1864. The property’s single wooden farmhouse and barn became the site of not only Harold’s upbringing, but also his academic inspiration.

As his biographer wrote, “[the] farm had given him his instinct for simplicity, his capacity for continuous hard work… and his ability to communicate understandingly with people in a wide variety of walks of life.”

When Harold died in 1952, his brother, Sam Innis (photographed on the next page) became the legal owner of the family farm, a role Sam was less than eager to adopt. Instead of letting the farm go, Sam allowed the rural property to be acquired by the Harold Innis Foundation. The college formed the Foundation in 1968 and the acquisition of the farm was its first activity.

The project was billed as an attempt to preserve the legacy of Harold Innis’ life and work. As a reporter in the Woodstock Sentinel Review wrote in 1971, “little is known about Innis despite his contribution because he had an uninteresting personality.” The act of acquiring the farm sought to change this.

The property was meant to house a library of Harold’s works and a conference centre for symposiums on his literature, as well as serve as a space for rural retreats for those working on his favoured topics of Canadian political economy and communications.

It was meant to be a “Pugwash of the future,” charged Marshall McLuhan, a student of Harold’s and the media theorist accredited with predicting the rise of the Internet. Pugwash was famous at the time as a rural conference centre in Nova Scotia, which hosted numerous high-level philosophic talks about nuclear weapons.

However, the farm did not come cheaply – nor easily – to the foundation. In 1969, the 120-year-old farm house on the property was in bad need of repairs, and after the acquisition of the property, the cost of constructing appropriate facilities and hiring live-in caretakers was not cheap. In that first year, the foundation raised $16,000, enough to purchase the property with a 6% mortgage. In the years that followed, the foundation would need an additional $150,000 for capital costs.

The group of city slickers who examined the site immediately after its purchase also seemed to face a number of physical barriers. In February 1969, Robin Harris, the principal of the college at the time, told the London Free Press, “We haven’t done a thing to anything on the farm. We still can’t get into the silo, the door is barred on the inside.”

These challenges were overcome by 1971 and in the fall of that year, a 25-person conference centre was opened on the site with two resident managers living in the historic farmhouse. 90 percent of the farm that was considered arable was also rented to a local farmer who grew corn on the fields.

In those early years, it cost $20,000 a year to operate the farm with $6,500 contributed through membership fees to the foundation and the rest from rentals and donations. Ads were quickly printed in university publications, including the one pictured on the next page from the June 1972 edition of Voice, a newsletter published by the Association of Part-Time Students. Early users of the farm included Innis College staff members, numerous faculty associations, St. Stephen’s in the Fields Church, and urban and film field courses.

The farm also quickly became a hit with the Oxford County locals and newspapers alike. Numerous articles were published throughout the 1970s about the farm’s first caretakers, Campbell and Grace Laker, who lived on the farm with their two young children.

One journalist in particular remarked on the angular building of the site’s conference centre as being “unique among the unimaginative square barns and farmhouses of the county.”

The centre played host to local talks of regional importance, perhaps marking the beginning of Innis’ long tradition of incorporating community with campus. When the Herald spoke to Roger Riendeau, Innis College’s unofficial historian, former vice-principal, and current professor in the Writing and Rhetoric Program about the farm, Roger noted how the site became an unofficial representative of the university in Oxford County. Early events at the farm included a forum on regional governance, and another on the tobacco industry, for which Oxford County is Canada’s heartland.

A Place for Students

Perhaps community and faculty uses of the farm were truest to its original purpose – to explore topics important to Harold Innis. That said, students’ use of the farm represented the embodiment of the foundation’s secondary goal: “to employ the farm to help guests gain a perspective lost in the urban university environment.”

Students’ first encounters with the farm came as a part of what was called “Woodlot Weekends.” Through Harold’s own concern for the land, the foundation established a program with the Ontario government in which parts of the lot would be reforested. Students would spend the weekend cutting down old growth trees and thinning the woodlot at the back of the farm, preparing the site for later planting. By 1972, 11,000 seedlings had been planted on the site.

Chris Glover, an Innis alum and current Member of Provincial Parliament for Spadina–Fort York, fondly remembered the farm when he spoke to the Herald last week. Chris began his university career as a Victoria College student – however, during the summer prior to his first year at U of T, he transferred to Innis after falling in love with the pinball machines located in the college’s basement and the cheap – sometimes free – beer that came from the machines’ profits. Chris recalled traveling to the farm with twenty others on weekends with stereo and David Bowie cassettes in hand.

“There was a real sense of community among those who visited the farm and we all loved going up there,” Chris told the Herald.

Soon after the farm’s inception, the ICSS established a Farm Representative position on council who was responsible for organizing weekend trips to the farm. Visiting the farm was also a tradition of ‘Innisiation,’ the name of Orientation Week at the time.

“This facility [the farm] (because of the fun people and relaxed atmosphere) has always been a favourite place for the students of Innis to escape to,” wrote Andrew Liebmann in the October 1984 edition of the Herald.

Andrew went on to report that the site was best for country walks, sleeping, and throwing a Frisbee around. He also noted, however, that a weekend at the farm wasn’t solely “low-key” and “mellow.” Students were encouraged to drink, dance, and “cut loose” in the evenings.

Indeed, the story of Innisfree is not without its more colourful elements. As the Herald reported in the 1980s, weekends at the farm were known to be ‘Dionysian’ in nature. Symptomatic of the 1970s and 1980s, weekend ICSS trips to the farm included everything from quiet walks in the forest to dancing, drinking, and debauchery.

Asked about the facility, Professor Riendeau noted that the farm was a place for students to escape to the countryside from the city. The ICSS would have parties, as 19 and 20 year olds do, but nothing was ever unsafe, the police were never involved, and life would go on.

Even Chris Glover noted that while Innisfree was often simply known as “the farm” during his time as a student, the adjective “free” certainly describes students’ experience there.

It seems the only people who were upset at the time were the site’s astonished caretakers, Henry and Norma. Roger told the Herald he remembers having Monday morning calls with the couple, in which the weekend’s events were described.

“I hated those Monday morning phone calls,” said Roger.

The Legacy

In 1972, the foundation faced something of a financial crisis. The Herald found numerous letters from then-principal, Peter Russell, to alumni requesting donations to help with the capital costs of the farm. The money was raised and the farm survived another 16 years.The financial difficulties and administrative barriers that the foundation faced by the late 1980s, however, could not be so easily surmounted.

New challenges faced by the foundation were compounded by two facts, noted Professor Riendeau.

First, the farm was becoming an increasing liability. In a changing legal environment both the university and foundation recognized they were in a more litigious society – the farm opened both the college and the foundation up to lawsuits.

Second, by 1989 the farm required monumental repairs, including to the aging historical house on the property and the roof of the conference centre.

The farm was sold in July 1988.

Roger said the foundation was “relieved to be out of the property management business.”

Soon after the farm was sold, a new owner – a Guelph University music professor named Doug Pullen – attempted to continue the conference centre, renting the space to the ICSS twice a year at the same place as when the site was owned by the Harold Innis Foundation.

Jim Shedden, Executive Secretary of the foundation at the time, warned students “not to blow it.” In a humorous note in the Herald, Shedden wrote, “don’t put holes in the wall, pour beer on the carpet, or rip the toilets out of the wall.” Although it is unclear if this ever happened, a few years later Pullen no longer found the event-business profitable and the farm was sold to a ginseng farmer.

Roger described returning to the farm in the 1990s when the foundation attempted to establish a connection with its current owner. Unfortunately, no plan would come to fruition.

Today, little is known about the current owners of the farm or present use of the property. In 1988, the township of Norwich declared Harold’s former house a heritage property under the Ontario Heritage Act. A plaque commemorating Harold’s life and works remains on site.

Through a detailed analysis of historic maps, hand drawn diagrams, and satellite imagery, the Herald was able to confirm that little has changed in the physical landscape of the property. The silo from the original barn now stands alone in the front field. A hydro-field still halves the property, separating the buildings from the bulk of the property’s largest fields. The reforested woodlot at the back of the property remains sizable. The most noticeable change appears to be the installation of a pool by the current owners sometime between 2009 and 2013.

As for the foundation, the revenues from the farm allowed the Harold Innis Foundation to serve students better. Roger noted that instead of helping just a few, the sale of the farm and the foundation’s return to financial stability ensured the body could function and assist students for decades to come. The foundation continues to issue three sizable student scholarships a year including the J.J. Stern award, the TA Reed Award and the Harold Innis Award.

In 2018, Innisfree has long since left the collective consciousness of the college’s students, yet the legacy of the farm continues as the funding source of numerous student scholarships maintained by the Harold Innis Foundation, the origin of the college’s proud history of blending community and campus life, and as a representation of Harold Innis’ own thoughts and scholarship.

The Herald is grateful for the assistance of Ben Westrate, Roger Riendeau, and the Harold Innis Foundation who made this article possible, and to MPP Chris Glover, whose fond memories of the farm inspired the piece. The historical plaque on the site of the farm can be visited in Norwich county at 225947 Otterville Rd, Otterville, Ontario.

Hello Every one

My wife and are the Proud Owners of the Herald Innis Farm since 2014 we have done some changes to the conference centre which is now owner home. but the lay out is very much the same as it was in the photos in this brochure and the resemblance is clearly seen .the old farm house has been cleaned and repainted in the inside but was left original as the Innis family has left it. we wanted to keep the Innis Farm historical tradition going. we now rent out the house for Vacation rentals. so people can come and see were the Harold Innis Family had farmed and lived.and later the university of Toronto had purchased. if you know or are interested to spend a week or more please send us an email to Innisfreefarmotterville@gmail.com there will be pictures on an airbnb site in the near future.

Thanks from

Carl & Lynda Koudys

Thanks for this interesting look back! I am an Innis and I remember visiting the conference centre as a kid–and I remember my family members joking that the farm eventually lived up to its name and became totally free of Innises. Also as a U of Toronto graduate in English I must point out that the poem “The Lake Isle of Innisfree” is written by W.B. Yeats about a location in Ireland. The Ontario farm is named after the site in the Yeats poem.