The Other ‘Once Upon a Times’ A History of Beginnings

Whether it makes you think of Disney movies or bedtime stories, there is no call for a child’s attention quite as effective as “Once upon a time…”

Its vagueness ensures surprise; its familiarity promises comfort. But before the saying became a herald for happy endings, it was the opening line for English poets and bards—a mark of the oral storytelling tradition. The earliest use of the phrase dates back to at least 1380, having been documented in the Middle English romance Sir Ferumbras; however, its oral history likely precedes this poem. In the centuries that followed, the idiom would be adopted by novelists like Dickens, who began A Christmas Carol with, “Once upon a time—of all the good days in the year, on Christmas Eve—old Scrooge sat busy in his counting-house.”

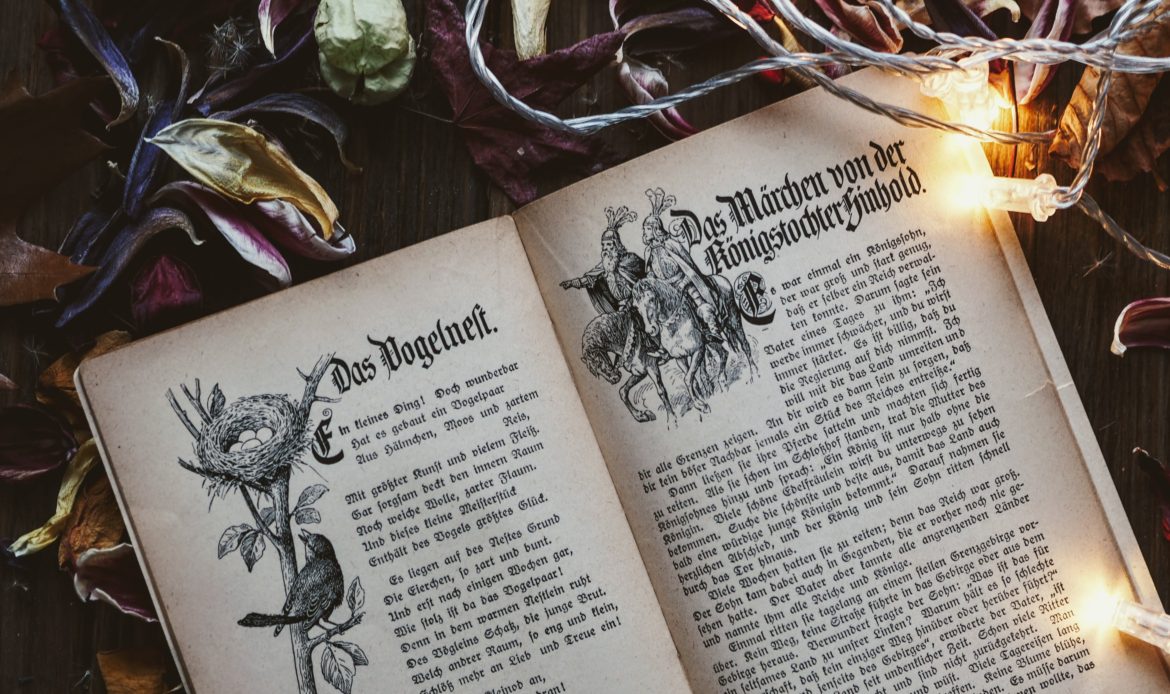

Yet, it was not just the English who began their stories this way. French writer Charles Perrault, the father of fairy tales, began classics like Cendrillon (Cinderella), and Le Petit Chaperon Rouge (Little Red Riding Hood) with “Il était une fois…” (once upon a time). A similar translation can be seen in Hans Christian Anderson’s “der var engang,” meaning “there was once,” and the Grimm Brothers’ “es war einmal,” meaning, “it was once.”

And the similarities are not confined to just Europe. The study of literature across cultures reveals unmistakable parallels in the narration of fables and fairytales: a formula of vague places, unnamed times, and promises of magic. So, what are the other ‘Once upon a times’ and how do they compare?

In the Tamil language, bedtime stories usually begin, “In that only place…” Whereas in Telugu the narrator will first lament, “Having been said and said and said…” The former touches on the singular power of fiction, while the latter invokes a storytelling lineage; yet the distinction proves how an opening might frame the mind of its audience. In parts of the Caribbean, oral stories begin with an engagement between the storyteller and their listeners; the narrator will call in Creole, “E dit kwik?” (I say creek), to which the audience will reply “kwak” (crack).

African folktales have a long-standing tradition of formulaic openings. In the Hausa language, stories begin with the call: “A story, a story. Let it come, let it go.” In Yoruba, it is more of a declaration: “Here is a story! Story it is.” Like ‘Once upon a time,’ these openings frame the experience of fiction by distancing the audience from reality; but unlike the classic English expression, they also seek to teach. The reader or the listener is not only being placed in the world of the storyteller, they are being taught something about the very nature of stories—about sharing them, carrying traditions through them, and remembering that they are, by nature, untrue.

This undercurrent of instruction is made explicit in the Chilean opening: “Listen to tell it and tell it to teach it.” It is not as playful as its African counterparts, nor as soft as its English equivalent; yet it tells us something about the intentions of the storyteller, colouring the narrative with an earnest sincerity. Other cultures have taken more humorous approaches, luring the audience in through absurdities. In Catalan a story may begin: “In a corner of the world where everybody had a nose…” and in Korea: “Once, in the old days, when tigers smoked…” The random images encourage laughter, while subtly disconnecting the listener from a world where sensibility is key.

The Polish fairy tale tradition, though not as comedic, also uses imagery as a device of disconnect: “Beyond seven mountains, beyond seven forests…” It is near-identical to the opening in certain Indian stories, which begin, “Beyond seven rivers, beyond seven seas.” The audience is immediately swept away from their contemporary present into a vague wilderness, mirroring the spirit of unknown ‘time’ in ‘Once upon a time. ’ A lack of clarity seems to be a prominent feature of these openings, but none are so deliberately obscure as the traditional Arabic: “There was and there was not,” which has similar translations in Farsi, Maltese and Romani.

On the strange similarities between storytelling traditions, Dr Lucia Sorbera — head of the department of Arabic language and culture at the University of Sydney— explained: “Borders are a very recent invention historically. From the 12th to 16th centuries, there was a particularly rich exchange between Asia, North Africa, Europe and the Middle East… This allowed the circulation of knowledge and language.”

If the fairytales that have shaped the mythos of humanity are products of a cross-cultural phenomenon, of a social transmission, then the children who now listen to them ought to know that there is more than one way to begin a great story. The ‘Once upon a times’ of childhood may always hold sentiment to those who listened to them, but perhaps the key to realizing the full potential of storytelling is to become immersed in its diversity.