The Sandman: Storytelling that Transcends Genre

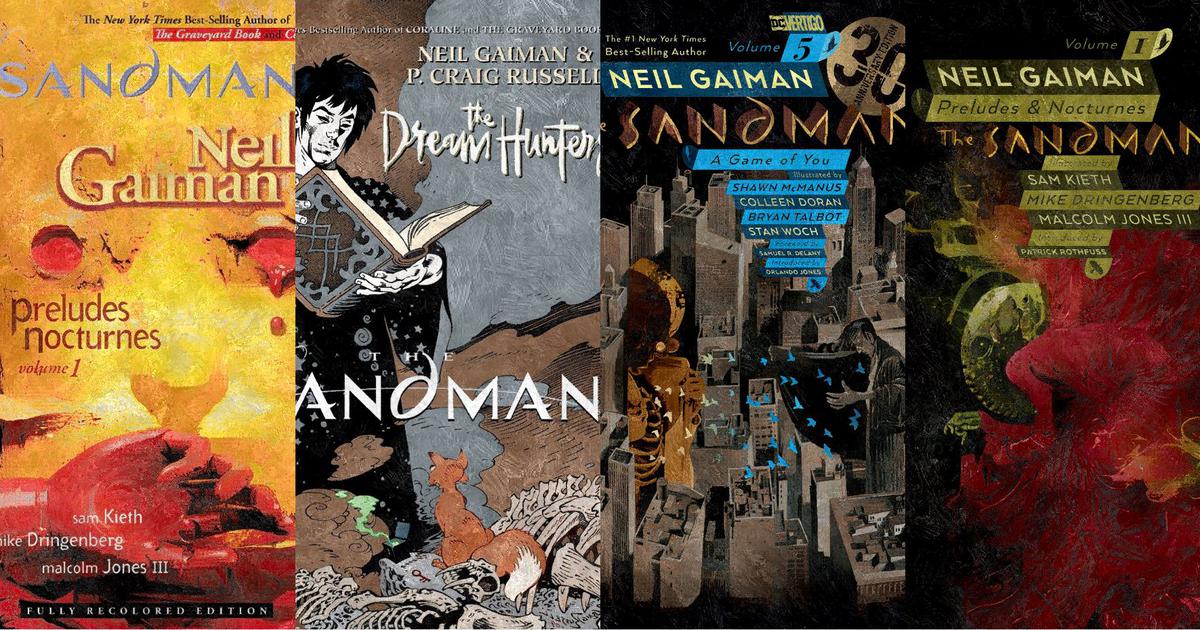

I started reading Neil Gaiman’s The Sandman with absolutely zero context. I’d read Good Omens and American Gods, so I was familiar with Gaiman’s whimsical style and self-conscious humour, but I wasn’t aware of the impact he’d had on the comic book industry or of The Sandman’s profound success. In truth, I saw a post about the upcoming Netflix adaptation and the dark, foreboding figure on the cover intrigued me enough to buy the first volume: Preludes and Nocturnes.

The story begins with Roderick Burgess, an ambitious occultist, who is trying to capture Death, one of the seven Endless beings that have existed since the beginning of time. The ritual doesn’t go as planned, and Burgess finds himself the inadvertent captor of Death’s younger brother: The Dream Lord Morpheus. Imprisoned for 60 years and stripped of the magic objects imbued with his power, Morpheus does not realize that his absence has been a catalyst for chaos in both the dreaming and waking worlds.

When he finally manages to escape, the Prince of Stories embarks on a quest to reclaim his lost power, encountering many familiar faces along the way. Fans of DC comics will recognize John Constantine, Dr. Doom, Martian Manhunter and the occasional Justice League reference. We are also introduced to a host of new, equally-riveting characters, including Lucifer Morningstar, Gaiman’s deliciously wicked and unexpectedly polite incarnation of the devil.

The journey is reminiscent of a Homeric epic, complete with a visit to the Underworld, divine intervention, and a less-than-perfect hero. Morpheus can be narcissistic, petty, and unforgiving, but his experience is a humbling one, and we witness his subtle change continue throughout the following nine volumes.

I picked up the next book almost immediately—not because the first one ended on some massive cliffhanger, but because the story is truly unique and I just had to know what happened. The characters sneak up on you, drawing you in with their witty banter and unresolved schemes. It is elegantly narrated, with just enough ambiguity to keep you guessing and just enough clarity to blend Gaiman’s mythology seamlessly with our reality. It has elements of the uncanny, of Greek tragedy, and Arabic anthologies. It transcends genre.

Gaiman crafts an intricate web of characters, plot-points, and themes, with the Dream Lord at its very centre. Certain volumes are structured chronologically as Morpheus navigates the mortal plane or his dysfunctional family, while others function as inset-narratives, flashbacks of his past. In some volumes, like The Doll’s House or A Game of You, Morpheus is not even the main character. Instead, he appears at the end of each issue, or he scarcely appears at all.

You might reach a point where you ask yourself, “Where is this going?” Have faith. Everything is connected, and when you do begin to connect the dots, when you start to see the invisible threads Gaiman has so cleverly weaved, it is nothing short of brilliant.

For those who enjoy audiobooks, audible has released the first part of The Sandman adaptation narrated by Neil Gaiman and a cast of actors, including Taron Egerton as Constantine, Kat Dennings as Death, Michael Sheen as Lucifer, and James McAvoy as the titular Dream. McAvoy captures Morpheus’s dry humour and unexpected kindness perfectly, and the soundtrack provides a stunning backdrop for the talented cast. Although the production only covers volumes one to three, the series has been renewed for two more parts to complete the saga.

If the audiobook’s speedy success is proof of anything, it’s that The Sandman is timeless. The first issue debuted in 1988, and over thirty years later, it continues to be relevant. So my advice to anyone who loves a good story is simple: Read (or listen to) The Sandman. I promise you won’t regret it.